HR Guide to the EU Pay Transparency Directive: Expert answers

As the EU Pay Transparency Directive moves closer to implementation, many organisations are seeking practical clarity on what the new rules will mean for everyday HR operations.

To help HR teams prepare with confidence, we developed this expert Q&A together with Piotr Żukowski, attorney-at-law and labour law specialist. It addresses some of the most common questions organisations are asking as they prepare for upcoming transparency requirements.

While national legislation will ultimately define the exact obligations, understanding the Directive now allows organisations to build stronger structures, improve documentation, and reduce future compliance risk.

This article answers the most frequently asked HR questions about the EU Pay Transparency Directive, including what counts as pay, what employers must disclose, potential risks, reporting requirements, and how organisations can prepare.

Key dates HR should know

The Directive introduces a phased timeline that organisations should already have on their radar. Understanding these milestones helps HR teams plan preparation activities early and avoid last-minute compliance pressure.

Scope of the Directive: What counts as pay and who is covered

Before preparing for compliance, organisations need clarity on two foundational questions: what qualifies as “pay” and which workers fall within the scope of the Directive.

What counts as “pay” under the EU Pay Transparency Directive?

Under the Directive, “pay” includes not only base salary but any form of remuneration a worker receives from their employer, whether paid in cash or provided as a benefit.

This means organisations should consider the full compensation package, including:

- bonuses

- overtime pay

- allowances (such as housing, food, or travel)

- compensation related to training

- statutory payments (for example sick pay)

- occupational pensions

- payments linked to termination

In practice, this definition covers both fixed and variable components of compensation.

According to Piotr, equity may also fall within this scope if it functions as an incentive or loyalty mechanism similar to remuneration.

For HR teams, this means preparation should go beyond reviewing salaries alone — and extend to all elements that contribute to an employee’s total compensation.

Does the Directive apply to contractors or only employees?

The Directive applies to workers who have an employment contract or employment relationship as defined by law, collective agreements, and/or practice in each Member State.

In Poland, for example, the legal regulations (still at draft stage right now) will most likely apply only to employees, and not contractors or B2B collaborators.

Because implementation will vary, organisations operating internationally should closely monitor national legislation.

What employers must disclose — and when

The Directive strengthens employees’ rights to pay information and sets clearer expectations for employers. Understanding what must be shared — and under which circumstances — is essential for reducing organisational risk.

What information must be shared with employees upon request?

The Directive doesnotcreate an obligation to disclose individual salary details of other employees.

Workers have the right to request and receivein writing:

- information on their individual pay level

- average pay levels, broken down by sex, for categories of workers performing the same work or work of equal value

What does “work of equal value” mean in practice?

The Directive distinguishes between work that is the same and work that is of equal value — and the difference matters when assessing pay fairness.

Piotr explains this with a practical example:

If several marketing specialists perform roles that are comparable in terms of responsibilities, experience, workload, and other objective criteria, their work would be considered both the same and of equal value.

However, if differences appear — for example in financial responsibility, geographic context, or level of experience — the roles may still be the same type of work, but no longer of equal value.

The reverse can also happen. For instance, an organisation may classify a marketing specialist and an IT systems administrator within the same pay grade because their roles contribute similar value to the business. In this case, the work is of equal value, even though it is not the same type of work.

For HR teams, this highlights the importance of clearly defining job criteria and documenting how roles are evaluated — so pay differences can be explained in a structured and objective way.

What time period should the data cover?

The Directive does not specify a fixed period (such as the previous year or last 12 months). According to Piotr, this will likely be clarified in national laws.

In practice, a “snapshot” view — showing current pay levels — should generally be sufficient. If certain pay elements cover longer periods (for example annual bonuses), the most recent available data should be used.

Employees may also request clarifications if they believe the information provided is incomplete or unclear.

For HR teams, this means it’s important to ensure data is accurate and explainable at any given moment.

What level of pay difference between employees is considered legally justifiable?

According to the Directive, acceptable criteria for wage differentiation include:

- skills

- effort

- responsibility

- working conditions

- other factors relevant to the specific job or position

What does “effort” mean in practice?

Effort can refer to the intensity, workload, or pressure associated with a role — even when job titles are similar.

For example, Piotr explains:

In an IT support company, one employee may handle a high volume of daily requests — for instance 16 tickets a day — while another supports a quieter environment with fewer requests. Even if their roles are similar, the higher workload and constant pressure can justify higher pay based on the effort involved.

For HR teams, this means that differences in workload or operational pressure can be legitimate reasons for pay differences — as long as they are documented and applied consistently.

Here are several practical examples of objective criteria:

- Geographical differences— roles in large cities may involve a greater workload or pressure.

- Scale of financial responsibility— serving a key client with a multimillion-value contract may justify higher remuneration.

- Time pressure and operational risk — roles where delays create serious consequences may warrant higher pay.

Pay differences must be grounded in objective, job-related factors — not subjective decisions.

Complaints, disputes, and employer responsibility

Greater transparency is expected to reshape how employees discuss compensation. While the real impact will depend on national legislation, organisations should prepare for more structured conversations around pay.

What could potentially trigger employee complaints, disputes, or audits?

According to Piotr, many workplace conflicts may appear from situations where employees lack clear information about how their pay is determined — particularly if they discover differences compared to colleagues performing similar work.

Greater transparency may help reduce uncertainty, but it may also encourage employees to ask more questions about pay decisions.

For HR teams, this means the ability to clearly explain:

- how remuneration is structured

- which criteria influence pay

- how progression is determined

will likely become increasingly important.

When employees understand how pay decisions are made, it reduces confusion and leads to better conversations about compensation.

What penalties may apply if a company does not comply?

The Directive itself does not set specific fines or penalty amounts.

Instead, each EU country will define its own penalties when implementing the Directive into national law. These penalties are expected to be:

- effective

- proportionate to the breach

- serious enough to discourage non-compliance

In practice, this means the consequences will depend on local legislation and the circumstances of the case, including whether the issue was isolated or systemic.

For HR teams, the key takeaway is that preparation matters — having clear structures, documented criteria, and accurate data will help reduce compliance risk once national rules are in force.

Preparing for compliance

Although many national laws are still being finalised, preparation does not need to wait.Organisations that begin reviewing their structures, data, and processes early are typically better positioned to adapt once requirements become legally binding.

What should HR teams prioritise if they are not fully prepared today?

Piotr advises that the first step is to verify whether national legislation transposing the Directive has been enacted.

The Directive itself does not create direct obligations for private companies — local law will be decisive.

If legislation is still in draft form, organisations should monitor developments closely to understand future priorities.

Where regulations are not yet in force, an important starting point is data gathering, including:

- what positions and grades exist

- the current pay structure

- objective factors influencing remuneration (e.g., geography, workload)

Preparation often begins with understanding your existing structures and data.

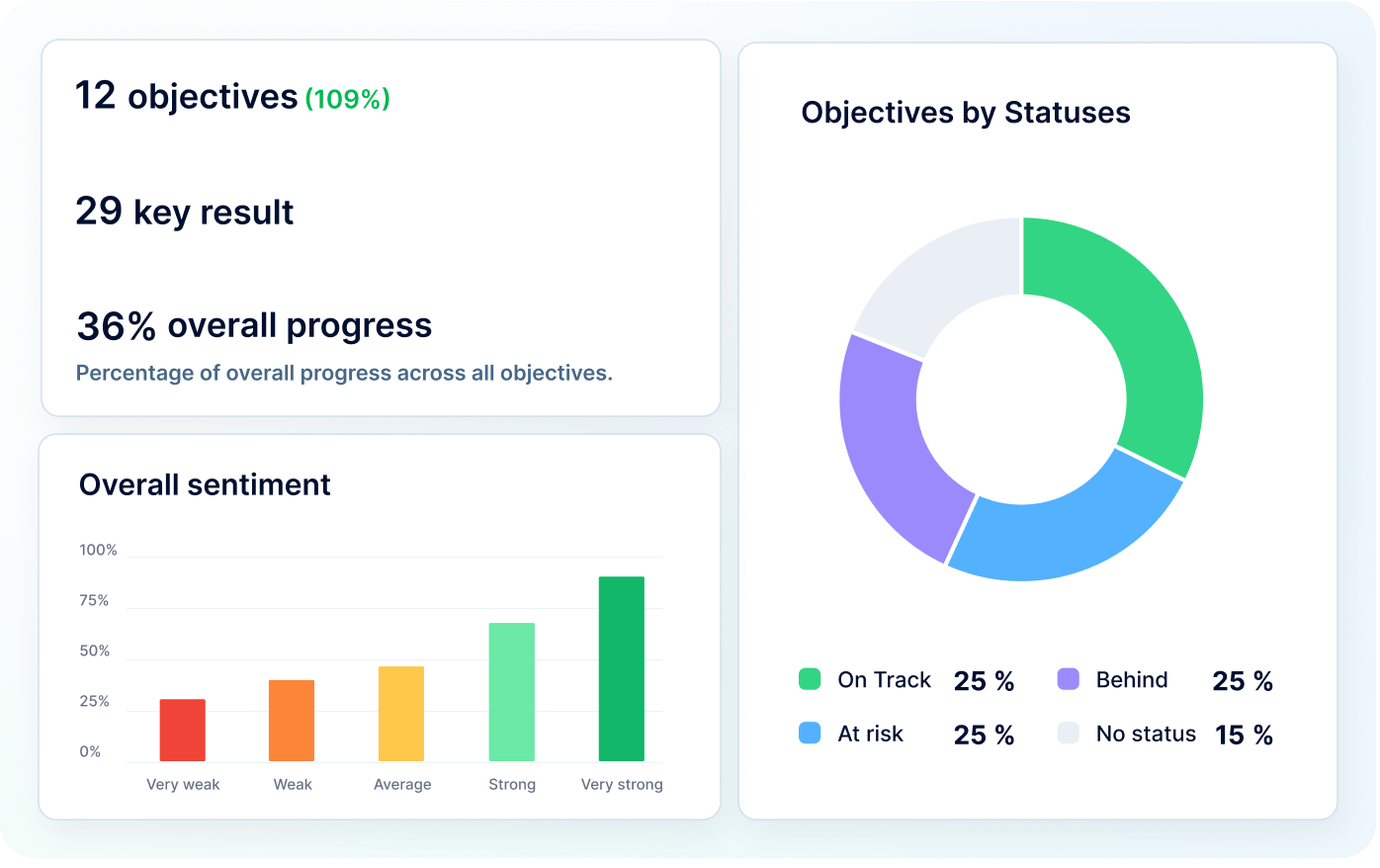

What data must be accurate for gender pay gap reporting?

The Directive requires reporting on multiple indicators, including:

- the gender pay gap

- the gender pay gap in complementary or variable components

- the median gender pay gap

- the median gap in variable components

- the proportion of female and male workers receiving variable pay

- the proportion of female and male workers in each quartile pay band

- the gender pay gap by worker categories performing the same work or work of equal value

These categories must be grouped using objective, gender-neutral criteria.

How should companies operating across multiple EU countries approach consistency?

Piotr recommends starting with a clear overview of the requirements set out in the Directive at the European level.

The next step is to review local laws in each country where the company operates and check whether they introduce any differences.

If national regulations closely follow the Directive, organisations can often apply a consistent approach across locations. This is a common method when EU Directives are implemented into local law.

However, if countries introduce variations, each situation may need to be assessed individually. In some cases, it may be possible to design processes broad enough to meet multiple national requirements — but this will become clearer once more countries finalise their legislation.

What this means for HR teams

Across all expert insights, one theme is clear: preparation starts with structure, documentation, and reliable compensation data.

Organisations that begin early often gain more flexibility to adapt as regulations evolve.

At PeopleForce, we continuously monitor regulatory developments across Europe and collaborate with legal experts to provide practical guidance for HR leaders preparing for pay transparency requirements.

For a deeper look at practical preparation steps, explore our full guide to pay transparency readiness.

Key takeaways for HR leaders:

- The Directive defines pay broadly, covering both fixed and variable compensation.

- Employees will gain stronger rights to request pay information.

- Objective criteria must support pay differences.

- Reliable data will be critical for future reporting obligations.

- Early preparation helps reduce compliance risk.

You can also speak with a PeopleForce expert to better understand how your current HR setup supports future compliance.

All expert commentary in this article is provided by Piotr Żukowski, attorney-at-law specialising in labour law. The answers are provided for informational purposes only and should not be treated as legal advice. Always consult your legal counsel when making compliance decisions.

Get started with PeopleForce today

Automate your HR routine to create a high performance culture in your company. PeopleForce is your best HRM alternative to stay business driven but people focused.

Recent articles

Get Ready for the EU Pay Transparency Directive with PeopleForce

Discover the key obligations of the Pay Transparency Directive and see how PeopleForce helps organisations prepare the structures, processes, and data needed to comply with the new requirements.

Comparing the top 10 HRM systems: How to choose the best one?

Struggling to choose the right HRM system for your team? Want to know which platform offers the best value, features, and support? We’ve compared the top 10 HRM solutions to help you decide — with real user ratings, pricing breakdowns, and key use cases.